IRIS

Inscrutable and Marvelous "Houses" in the Paintings of Trisha Orr

by Lisa Russ Spaar

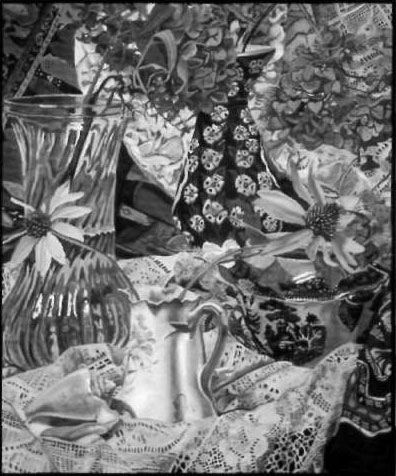

Turkish Vase (1994) by Trisha Orr. oil on canvas, 24"x20".

Time to plant tears, says the almanac. The

grandmother sings to the marvelous stove and

the child draws another inscrutable house.

—Elizabeth Bishop

The last three lines of Elizabeth Bishop's "Sestina" evoke the simultaneous presence of objects, self, and loss that exist even—or especially—at the heart of family life. This sestina's cumulative chord of distinct but equal voices, its concerted collage of incrementally repetitious detail, centers around the paradoxical "inscrutable house"—an image embracing both enigma and domesticity. Like Bishop in her sestina, Trisha Orr uses multiplicity, repetition, and patterning- the embellishment of canvas, her "text"—to express worlds charged by both bodily and mysterious, domestic and exotic presences. In doing so, she gives

Page 15

shape and wholeness to the particular interior and exterior spaces women inhabit, both physically and psychically.

Both Orr's earlier paintings—magnified studies of precariously balanced and nesting shells and her more recent, opulent canvases, in which rich, varied textures and patterns seem almost to precede and supersede form, pay rapt attention to the things depicted. These are domestic objects—the shells are themselves houses; the newer paintings give us also vases, jars, cut flowers, cascades of draped fabric, quilts, baskets, tureens—the familiar and peculiar private objects of the cupboard, linen closet, garden, attic, and cellar -historically or personally charged objects that themselves hold or house things. The objects in these ensembles are bathed in scrim-like, invisibly woven light, without nostalgic shadow, chiaroscuro, or the foreshadowing of dissolution—without, even, the context and scale a present human figure might lend. The objects govern, and even become, the lenses through which we view them a swatch of striped table cloth, for example, is received through eye, canvas, frame, glass bowl, cut-glass vase, and a prism of standing water. It is in objects and their relationships depicted in these still lifes that the woman watching may also begin to locate a thrillingly "unslill" sense not only of place, but of self, as well.

Both the earlier and more recent paintings, then, give us each thing of the world as part of a definite but kinetic whole -what painter and art historian David Summers calls Orr's "sensuous unity," an integrity in which each object seems "to turn into something everywhere." That each object possesses a distinct, quietly charged presence is especially surprising in the newer work, whose rich, luxurious colors and exotic patterning could seem busy, competitive, even muddy, but don't. This unhierarchical multiplicity, this spirit of different equivalence, and the three-dimensionality of the work give the paintings an energy that is assertive but not aggressive, and distinguish Orr from other painters who have employed decorative patterning, materiality, and all-over painting methods less democratically in their work. And in this way. interestingly, Orr's paintings embody perceptions about what feminist Sara Ruddiek calls "maternal thinking," an impulse toward world synthesis and "world repair" characterized by "a selfless respect for reality" and the

Page 16

"invisible weaving" humans do to house themselves in a world governed by necessity and change—a world, as Mrs. Ramsay says in Virginia Woolf s To the Lighthouse, "terrible, hostile, and quick to pounce on you if you give it a chance."sive and imminent danger are Orr's shell paintings, large canvases depicting a coiled shell— moonsnail or whelk—opening vulnerably toward the viewer but secretive and self-protective, almost fetally curled in a fragilely balanced "nest" of several halved scallop or clam shells. Some of the paintings focus on one of these nests of cradled shells; others contain three, four, even five clusters of them, in what Orr calls a "constellation or solar system." The colors in these pieces are closely keyed and peaceful; even the darks, the shadows, have white in them, and the surface is harmonious, seamless, bathed in an all-over, silvery light as present as the shells themselves.

But the paintings themselves are not peaceful. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard writes that "an empty shell ... invites day-dreams of refuge," that "the shell [is] the clearest proof of life's ability to constitute forms," and that the image of "inhabited stone" is a primal image as well as an indestructible one, an image acknowledging ultimate solitude. Orr uses magnification and a palpable surface to create the kind of wonder, the freshness, Bachelard finds possible in these often-symbolized objects. At the same time, the shells, these hardened "houses," these almost primordial husks from the amniotic sea, with their hidden centers and their missing halves, their delicate, tentative balancing, seem at once secretive and exposed. They appear human, huddled together like stricken family members. The cradled snail shells are ear-like, guardedly receptive, and the "sound" in the paintings, both familiar and eerie, is a hushed roar.

Bachelard points out that shells also invite dreams of emergence; in Medieval paintings, etchings, and jewelry, for example, "the most unexpected animals; a hare, a bird, a stag, or a dog, come out of a shell, as from out of a magician's hat." Hieronymus Bosch often shows shells in bestial, violent, or sexual transformations—travelers feasting and carousing in a mussel shell, for instance. One thinks of Aphrodite, or of sprouting seeds, or human in-

Page 17

fants—teeming, splayed multiplicity emerging from smaller "houses" that one could never imagine reentering. Orr's recent work seems to have sprung this way—rich, myriad, complex—from her earlier shell paintings. It is also possible to imagine these replete worlds existing inside the upward-opening shells, their mysterious ambages.

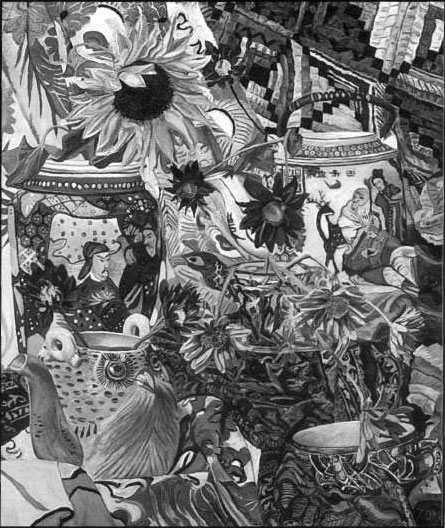

Encountering paintings like "Rumor of Delirium," for example, one is struck by the physical-ity, the slight magnification of objects, the three-dimensionality, the quilt-like gorgeousness of colorand texture. The sense of a mutable, transient world—the "floating world" of Japanese woodblocks, for example—is suggested here not only in the lyrical silks of the tulips, whose cupped blooms, in various phases of awakening, opening, and splaying, lilt and float on evanescent stems, but also in the embellished vases and teapots themselves, whose manifold scenes of domestic tranquility, solitude, strife, and transcendence speak to the tensions inherent in, and essential to, the experience of domesticity. On a teapot near the center of the paint-

Page 19

ing, whose spout forms a gilded, guardian dragon, a peaceful couple sit together, perhaps at tea. The curves and spouts and handles of the other objects around them, and the helical stems and the sun- and blood-red blooms that hover above, and the rich patterned cliffs and folds of quilted and brocaded mountains behind create a bower—a "house"—for this peaceful pair. At the same time, their lyrical equipoise of domesticity and love is unsettled by other images a solitary woman sails above a blue sea on a nearby vase; on another, two samurai warriors stand off; higher up the "mountain," on another teapot, a pair of wandering Taoist immortals seeks their own way. This playful, provocative use of implied and imbedded narrative, this "quoting" among psychically charged objects seems integral to Orr's vision in which the familiar and the strange, the domestic and the other-worldly, are brought into sensuous collision. At the same time that the viewer can almost smell the old and dying things—a waft of cedar in the linens, the dust of attics, the faint, rank odor of stems standing in water, she is caught up in the painting's "un-still" dancing between and among the objects assembled and the stories they suggest.

This opulent, present-tense bodying forth of unnostalgically assembled and rendered transitory objects creates a sense that the worlds portrayed are out-of-time, out of this world, like the lyric poem, evoked by Orr's titles, often borrowed from Emily Dickinson, in which the mutable world is momentarily arrested and transcended. But what's felt as strongly in these paintings is what's withheld and implied—the human narrative, the stories behind the hands that cut and arranged the flowers, that draped the cloth the makers of the assembled objects, the maker of the painting and, loo, the weddings, the deaths, the shared meals, the gifts, the travels, the inheritances, the dime store purchases, the chance junk-store "find" what Georgia O'Keefe called "barrels of bones" in short, the pains and pleasures, the lives of the humans connected with these eccentric and familiar objects. And it is in bringing into juxtaposition these powerful tensions—those gorgeously real and present in the objects, and those subjectively implied through context and reso-

Page 20

nance—that the paintings succeed in embodying the complex lives of the many generations of women to whom the assembled objects allude, and whom they honor and for whom they speak. For all of their detailed watching, the paintings acknowledge the privacy of the worlds they depict. And the locus, the center of energy in these works is the house—that historical nexus, invisible and elusive, safe and provocative—that place from which we issue and to which we can never fully return, that complex construct of physical object and emotional and psychological truth that both protects—or hides—and haunts, and invites.

An invisible but profoundly felt web—Orr's weaving of texture, light, pattern, and color—helps to knit these myriad "still" lives, but the weaving is not imposed upon the objects. This world-weaving, Ruddick's "world repair," comes up through the things painted, through the marriage of maker and object, and this portrayal of multiplicity without hierarchy, dominance, and editorializing is a chief gift of the work.

Page 21